It can take multiple lifetimes to build a village

Or, how I've tried to adopt a multigenerational mindset, part 2

If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, I would love it if you shared it with a friend.

A century and a half ago, my ancestor Jacob Hamblin settle in the American West. Hamblin was an early Mormon pioneer, and a colorful frontier character. I grew up hearing tales of his dealings with Native American tribes, and he was part of the extended family lore I inherited from my mom.

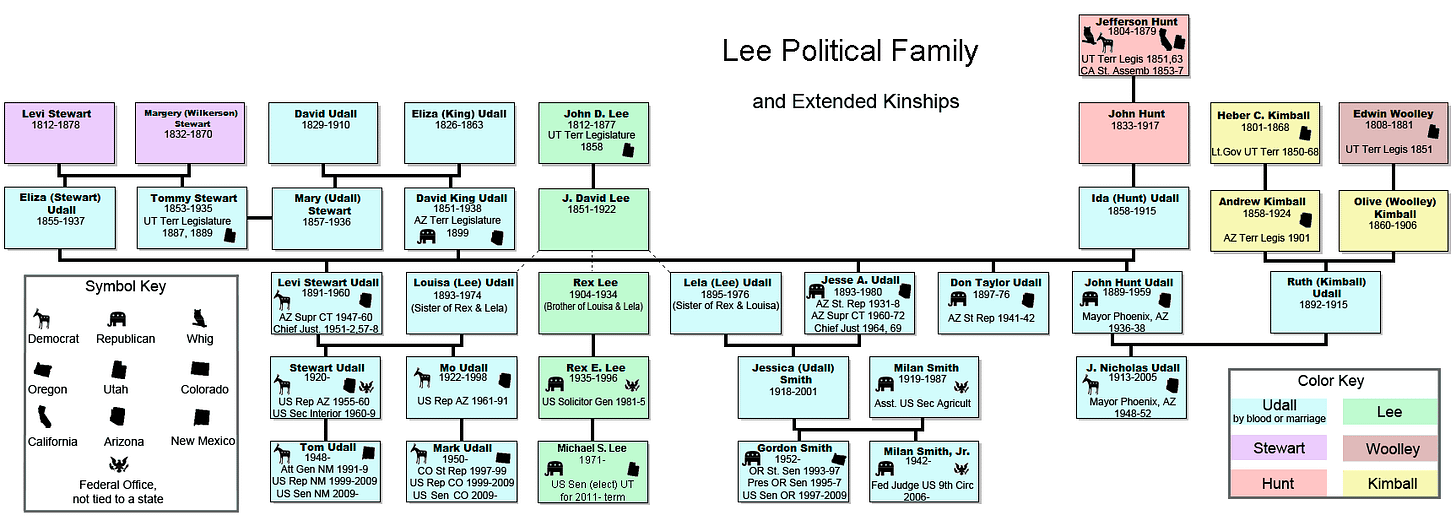

What I only learned as an adult, though, is that Hamblin is also the ancestor of a bunch of famous politicians: Utah Sen. Mike Lee, Utah Supreme Court Chief Justice Thomas Lee, former Oregon Sen. Gordon Smith, former Colorado Sen. Mark Udall, and former New Mexico Sen. Tom Udall, among others1.

I’m endlessly fascinated by the extremely divergent paths my own branch of Hamblin descendants took compared to the Lees and Udalls. Our two branches started out in the same place, but while my branch was bouncing around without much longterm vision, the Lees and Udalls were gradually making sure more doors opened up for each successive generation. Family meant opportunity.

I think this is a key part of what it means to have a village. In the case of the Lees and Udalls, opportunity meant political office. But don’t get caught up on the fact that they’re in politics. We could be talking about opportunity in manufacturing or technology or the arts. Having family that takes care of your kids is also an opportunity, and opens up still more opportunities. Even having a fulfilling social life is an opportunity.

And opportunity compounds over multiple generations.

Which brings me to today’s two-part thesis:

1) A village is permanent. If a group of people peters out after a single lifetime or, as seems even more common, a few years, a better metaphor than a village might be… an encampment. And there’s a reason the saying is “it takes a village…” not “it takes an encampment…”

2) It takes a really long time to build a village. I am personally convinced that it takes longer than a single lifetime. This has been a hard reality to swallow because it means I’ll probably never fully have the village I want or need — someone would’ve needed to lay the foundation for that generations ago, and they didn’t. If you’re reading this, and like me feel that there are some serious social gaps in your life, it may be too late for you, too. That’s because of decisions people made 30, 60, 90 or more years ago.

So, in my case adopting a multigenerational mindset means breaking that anti-village cycle and trying to think about what decisions I can make now that will benefit my own family 30, 60, or 90 years from now. I’m trying to think on a time scale of decades and centuries.

It takes a century

To better understand how compounded opportunity works, let’s dive a bit further into the Lee-Udall family. The first political Lee was John D. Lee, a member of the Utah territorial legislature in 1858. The family also includes Tommy Stewart, a member of the Utah territorial legislature in the 1880s, David King Udall, a member of the Arizona territorial legislature in the 1890s, and Jefferson Hunt, a member of both the Utah and California legislatures in the mid 1800s.

The tree above shows that over the next 150 years the family produced numerous political figures. But it’s worth keeping in mind that in the early years their positions weren’t particularly lofty. They were limited to regional offices in the West, a remote backwater at the time.

Let’s jump forward to Mike’s dad, Rex E. Lee, who was a U.S. Solicitor General, prominent lawyer, and whose name lives on today because there is an annual 5K race named after him in Provo, Utah. Rex’s political career began in the 1970s when he served as an Assistant U.S. Attorney General, and his various high-profile jobs over the years meant his sons hobnobbed with the families of people like Harry Reid.

It is probably no coincidence that both Mike Lee and Thomas Lee then went on to serve as clerks for U.S. Supreme Court Justices after they graduated from law school. Later, they had a series of high profile stepping-stone jobs until they ended up in their current positions (they were also both reportedly on the short list for the U.S. Supreme Court during the Trump administration.)

Don’t get bogged down here on whether or not you agree politically with the Lees. The point is not politics, but the fact that opportunity is generational. Mike and Thomas would likely not be where they are today if their family hadn’t been moving the chess pieces for five generations.

(For what it’s worth, the Udalls are Democrats, so there’s someone in this story for everyone.)

Compare the Lees’ experience to mine. When I graduated from college, I spent the better part of a year working low-paid, dead end jobs and applying for literally hundreds of other positions online. It occurs to me that two brothers who clerked for a U.S. Supreme Court Justice may have had more and better options to choose from than a person who spent their time futilely sending resumes into the digital void.

(To be clear, I’ve had a good life and have benefited from tremendous privileges. My own head start was considerable compared to people who, for example, didn’t have a chance to go to college or grow up in a supportive middle class household. I make the comparison not to point out my own disadvantages, which were few and far between, but rather because of my and the Lees’ common ancestor.)

In any case, I would rather my own kids had an experience that’s closer to the Lees: More options and better options, whatever those options may specifically be.

The Lee-Udall family shows how long it can take to do that. John D. Lee didn’t clerk for a Supreme Court Justice back in the mid 1800s. His kids weren’t U.S senators. It took five generations to get there.

It may be too late for you, but not for your kids

So let’s say I want to apply this principle to something more modest than political office. Let’s say the opportunity I’m aiming for is a family that provides cheap or free childcare.

Right now, that doesn’t work in my family. Traditionally, grandparents have been the top candidates to step in and help raise kids, but in my case my parents are both still in the labor force. They don’t have the ability to significantly increase their role in my kids lives. Ditto for my siblings. Ditto again for almost everyone I know. If you’re an adult with kids right now, the odds are your parents haven’t made the necessary plans to meaningfully take much of the parenting burden off your shoulders.

For a more communal approach to parenting, we would have needed an earlier generation to lay the groundwork years ago so that those of us who are around today could have the lifestyle and resources (and disposition) to coparent.

My friends who live in a family compound are a good example of this; today they have a robust support system made of several nuclear units. But when the first generation moved to that location they were just a single family without a compound. So, that first generation never got to enjoy the benefits of a compound at a time when it might have helped the most. They didn’t spend their childhoods surrounded by cousins. As young parents, they didn’t have siblings or nieces and nephews to act as built-in babysitters. Like foresters planting trees, the fruits of their labors are ripening at the end of their lives and will continue to do so after they’re gone from the earth.

Once again the point isn’t the specifics. Maybe the opportunity you want for your family is political office. Maybe it’s a compound. Or better job opportunities. I think at the most basic level, for most of us it’s just greater happiness. But whatever the opportunity, it either compounds over time as one generation invests in the happiness of people who won’t be born for decades, or it withers as each generation focuses on itself.

I have a lot of great and fascinating people in my family tree, but somewhere along the line they stopped making intergenerational investments. Each generation started anew, and our path diverged from the branch of the Hamblin family that did make those investments. My hope is to begin breaking that cycle and laying the groundwork that I wish my great- (great-great-etc) grandparents had.

Thanks for reading to the end of this week’s newsletter. If you liked it, consider sharing it. Or, if you hated still consider sharing it. A hate share is still a share.

This week’s headlines

Why 'stay-at-home parent' is a job title

"A lot of women end up dropping out of the labour market after giving birth to a child because they don't have any leave entitlements and the childcare prospects are not good," said Jennifer Bennett Shinall, a law and economics professor at Vanderbilt University.

"We force families into an impossible situation in this country."

Allow-parenting /or/ How I Learned to Let Go and Let Grandma

“But with alloparenting, especially grandmas, I expect that my daughter will have to learn that sometimes her needs don't come first. Grandma has to prepare the neighborhood newsletter, Abuela is taking night classes, and both of them, like Mary, have gardening to do. Those pre-Industrial parenting gurus stress the importance of teaching children to work alongside us rather than competing with our work or comprising the work of others, and grandparents, especially retired grandparents like my mom, are ideally situated to do so. Lucia learns that she is not necessarily the center of everything all the time, and she also gets a chance to learn some of those charming Montessori life skills alongside her grandparents.”

The Best Friends Can Do Nothing for You

“Decades of research have shown that it is almost impossible to be happy without friends. Friendship accounts for almost 60 percent of the difference in happiness between individuals, no matter how introverted or extroverted they are. Many studies have shown that one of the great markers for well-being at midlife and beyond is whether you can rattle off the names of a few close friends. You don’t need to have dozens of friends to be happy, and, in fact, people tend to get more selective about their friends as they age. But the number needs to be more than zero, and more than just your spouse or partner.”

The Lee-Udall family descends from a different Hamblin wife than my family.