Technology will not save you

There are no one-night stands for friendship

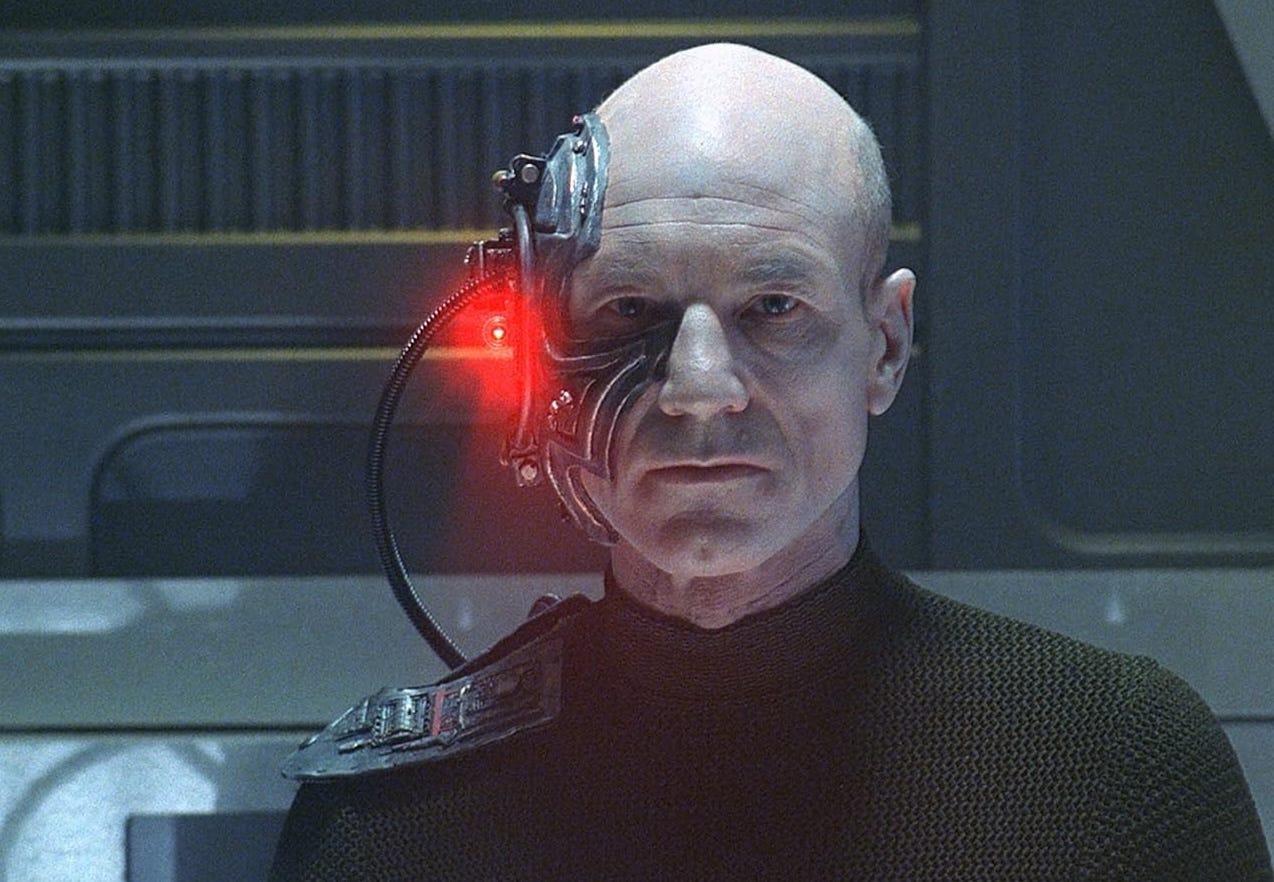

Thanks for visiting Nuclear Meltdown. Subscribe to this blog, resistance is futile.

There’s a telling anecdote about technology in a recent story from New York magazine. In it, Renate Nyborg — the former CEO of dating app Tinder — acknowledges that technology and dating apps have increased isolation.

“Technology was making loneliness worse,” Nyborg says, summing up an idea that has become widely accepted at this point.

But then, Nyborg offers her solution: An AI chatbot.

Nyborg specifically believes that the answer involves her chatbot company, which lets people practice their conversation skills. And I mean, sure. There’s nothing wrong with improving communication. But it’s hard to believe that anyone could make the case that technology is the problem and then propose that the solution is a junior varsity version of ChatGPT. How can problems stemming from technology be solved with more technology? If I get skin cancer, is the solution lung cancer?

The real answer of course is that technologists want to make a living and their toolset is technology. There’s a saying that everything looks like a nail if all you have is a hammer, and in this case we see that every problem looks like it needs an app when all you are is an app-builder.

But when it comes to issues of social connection, I think we’re heading down a fruitless path. Over and over, people correctly identify the obvious problems of isolation and loneliness, then inexplicably suggest that the solution is some new techno bobble. I don’t think of myself as a Luddite. I use technology all the time, and many of my posts on this very blog draw from conversations taking place on social media. Technology has its place and I’m not arguing that something like smartphones were a net positive or negative in general.

But when it comes to social connections, I would simply ask this: Where is the evidence that technology will solve the problems technology created? Because when I look around, I mostly see examples of the opposite.

Probably the best case study I can think of is Nyborg’s own former employer, Tinder. Certainly, there are a lot of people finding partners on dating apps — including people I know well. But the question is not if dating apps work in general. The question is if they have improved the dating experience relative to what came before.

I don’t think anyone is even trying to make that case. Among men, I most commonly see the argument that dating apps favor a tiny minority of elite users, leaving average Joes behind. And among women, there seems to be frustration with the behavior of those elite men. Think about the “West Elm Caleb” story from a few years ago in which a New York City employee of West Elm was apparently dating numerous women all at once — much to their chagrin. Dissatisfaction with this status quo has received copious news coverage.

Polling bears out the idea that dating apps are not necessarily making dating better; while app users are evenly divided on whether their experiences have been positive or negative, only a minority believe dating apps have improved the process. I met my wife before the Tinder era so I can’t speak from personal experience, but everything I’ve heard and read makes the dating app world seem borderline dystopian.

So in that context, I don’t know how anyone could look at a world filled with West Elm Calebs and think, “hey maybe we should do this for friendship.” Even the former CEO of Tinder doesn’t think that’ll work, though apparently the only tool at her disposal is a metaphorical hammer.

In reality, I would actually expect friendship tech to work significantly worse than dating technology. Even if finding a long-term partner on a dating app is difficult, they can be useful (apparently, I haven’t used them) for casual sex, and the polling shows that 40 percent of users have relied on the technology for casual encounters. So, good or bad, dating apps do facilitate something for which there is demand.

But there are no one-night stands for friendship. Experts such as Robin Dunbar have repeatedly found that friendships are built over time and require multiple interactions, often interactions that are unplanned. How does an AI chatbot provide that?

Dating apps are just one example that calls into question the prospects of friendship tech, but it’s also worth pointing out that the bigger technology ecosystem has had highly questionable impacts on social connections. Jonathan Haidt and others have repeatedly pointed out, for example, that mental health began declining at the same time smart phones proliferated, while the Bowling Alone phenomenon — or, people leading increasingly isolated lives — has worsened. I’ve touched on this idea a few times before and Haidt writes a free Substack exploring these ideas, so I won’t re-litigate the concept here. Suffice it to say that I cannot imagine the solution to problems connected to smartphone usage coming from… a smartphone.

And yet, people keep trying. This week Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg had a minor viral moment when he made Nyborg’s exact same mistake: He correctly noted that the average American doesn’t have enough friends and wants more. And he even acknowledged that in-real-life friendships are superior. But Facebook, equipped only with a hammer, apparently thinks the solution is artificial intelligence. As many others have noted in recent months, we are rapidly turning the premise of the movie Her — a man falls in love with his AI bot — into real life.

Smaller scale technologists fall into this trap as well. I recently read a Q&A on how to live near friends. I thought the subject, Phil Levin, was thoughtful and offered interesting insights. I envy his living arrangement. But what’s actually on offer, the thing I might use to replicate his apparently very social life, is a real estate app. Maybe technology actually can improve social connections by focusing on one very specific thing — housing, in this case — but it’s worth noting that somehow people managed to build literal villages for a very long time without an app. And when I think of the reasons my friends and I have all moved to different cities, an app or lack thereof is really not a part of the equation.

Like I said, I don’t think I’m an anti-technologist in general. But I’ve yet to see any tech solution to loneliness that doesn’t seem hopelessly doomed. A few seem like actual cons meant to scoop up venture capital. All of them strike me as examples of people trying to reinvent institutions rather than study what worked in the past.

Perhaps time will prove me wrong, and if so no one will be happier that we’ve solved this problem than me. But for now, I’d suggest we focus on reinvigorating the institutions that already have a proven track record of keeping loneliness at bay.

Thanks for checking out Nuclear Meltdown. If you’ve enjoyed this blog, consider sharing it with a friend.

Interacting with robots, or even actual humans, online, necessarily shields you from a lot of the awkwardness and mess of real human interaction. I think as a result we're sort of collectively losing our tolerance for feelings/experiences like embarrassment, or left-out-ness (?) or kicking yourself over saying the wrong thing! These normal, sometimes uncomfortable emotions are such a key part of being human and so inextricable from building genuine relationships of all kinds- but increasingly people can't tolerate them without devolving into anxiety spirals. So the tech reliance and the mental health struggles become a mutually reinforcing cycle, I think.

So glad you mentioned the movie "Her." It's excellent. And I keep wildly gesturing toward it anytime AI chatbots are even brought up. Did anyone take away a valuable lesson from that film...?