Thanks for checking out Nuclear Meltdown. If you enjoy this blog, consider subscribing.

Like a lot of people, I had my best friendships during my college years. I lived with friends. I went to class with friends. I worked with friends. I played in a bunch of bands with friends. Even a lot of my grocery store trips were done with friends. And the result was that I was really close to my friends at that time.

But that was years ago, and as happens with a lot of us I’ve drifted away from many of those people. I still count folks from that era as friends, but I never turn to them for help with my kids or for a move. I wouldn’t ask them for a ride to the airport. If the worst happened, I wouldn’t count on them to bail me out of jail.

What I noticed about my waning college friendships turns out to be something researchers have observed in friend relationships generally: Friendships take a lot of constant time and attention to maintain, and when that attention dries up so too do the friendships in many cases.

Curiously, however, that’s not really the case with family relationships. Indeed, Oxford evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar has observed that family relationships are “remarkably stable across time. By comparison, friendships were much more fragile. They depended on constant reinforcement to maintain”1.

I’ve seen this first hand. My college friends and I have (with a few exceptions) mostly stopped visiting each other. But I can tell from their social media posts that they still take time to visit their families. During the peak of our friendships, I think many of us preferred one another’s company to that of, say, our parents or siblings or cousins. But over the years it was the family relationships that survived even as the seemingly deeper friendships waned. As Dunbar put it, the family relationships remained “stable.”

But wouldn’t it be cool if there was a specific, formal way to make friendships function more like family relationships? So, I’m imagining a way for friendships to have that stability that Dunbar was talking about, even in the face of waning attention and maintenance. Imagine a world in which those college friends I’ve lost touch with aren’t relegated to the status of Facebook friends, but are more like, say, cousins: People with whom there’s a connection, and a potential support network, even if you only see them occasionally.

I unfortunately am not here to propose a specific solution. But I can think of some examples of relationships that sit in a grey area between friend and family.

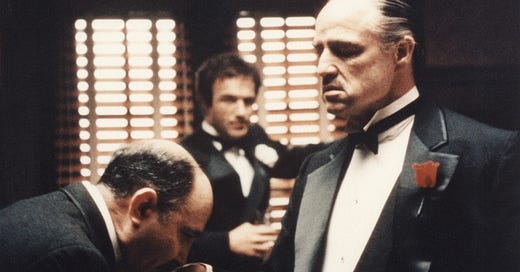

Take, for example, the mob. I’m not an expert on the mafia, but I do know that members of the mob can attain the status of “made man,” at which point they’re officially initiated members of the crime family.

It should go without saying that the mob is terrible. But I’m fascinated by the idea of “made” status because it’s a type of relationship that doesn’t exist in a lot of other contexts. Made men aren’t just co-workers or drinking buddies. They’re more than friends, but less than blood relatives. And with that relationship comes a support network. Unfortunately the mob uses that network to kill people and commit an assortment of other crimes, but I can imagine a hypothetical world in which non-criminal organizations have similar statuses2.

I don’t even have to try very hard to imagine such a world. The mafia as we know it today actually emerged in Italy during the 1800s as Italian society moved away feudalism. But it retains some echoes of that former institution. And glimpsing back into feudal societies, it’s easy to see that there were also types of formal relationships that don’t exist today. The feudal serf swore an oath of allegiance to the lord, who swore an oath to his lord, and so on up the chain of command. Again, these relationships were more than what we have today between friends or co-workers. But they also weren’t quite family either.

Feudalism overall sounds pretty terrible and oppressive. It’s great that we’ve moved beyond that. But I also can’t help wondering if there’s something to this concept of obligatory allegiance, and if it couldn’t be made more equitable. For instance, imagine if my college friends and I swore an oath that even if we went years without seeing each other, we’d always reconvene to drive the U-Haul when one of us moved. Not only would that make all of our moves easier, it’d also probably ensure that we maintained a higher level of emotional attachment as well.

That’s a silly hypothetical, but the point is that as the world has modernized, the spectrum of available relationships has flattened out. Some people are trying to expand these categories, for example with the idea of chosen family. The specific examples of this that I’ve seen are really cool and rewarding to the participants, but it’s a scattershot effort at the society-wide level. In other words, there’s no formal or official way to induct someone into your chosen family. There’s no widely agreed upon set of obligations that come with such status, or consequences for violating those relationships. There’s also no legal infrastructure to support these new kinds of relationships. If I die without a will, my blood relatives can make a claim on my estate (such as it is). But everyone else basically just has friend status, which is nothing in such a scenario.

The more I thought about this the more I wondered if there are examples of relationships that fall in-between blood relatives and friends (or other casual relationships such as co-workers)3, and which also don’t come from terrible institutions such as the mob and feudalism. I suspect there are actually lots from many different cultures, but one that immediately came to mind is godparents.

I don’t come from a religious tradition that has godparents (unfortunately), but the people I know who do have a kind of secondary support network. They are perhaps not quite as close to their godparents as to their actual parents but, significantly, it’s a relationship that is stable and durable in a way that many friendships are not. They can turn to their godparents for support even if they don’t see them often or expend a lot of effort maintaining the relationship.

I’m sure there are countless exceptions to these generalizations, but based on my rudimentary understanding of the concept from the people I know who practice it, that’s at least how it’s supposed to work.

Obviously godparents are not typically peers in the way that friends are, but the concept is at least getting closer to what I’m talking about. And what stands out to me about all of these examples is that there are institutional, and often ritual, components. You don’t just wake up one day and say you’re a godparent, or a vassal lord, or a made man. You’re initiated into those statuses. It’s a formal process. And they all come with specific (either written or implied-but-widely-understood) responsibilities.

Like I said, I don’t have a specific prescriptive solution. The institutions that once offered these kinds of relationships are either gone (feudalism, thankfully) or not hegemonic enough to make their vision of the world universally available. I could become a Catholic, for instance, but that wouldn’t really make the godparent idea more common, or open up space generally for other flavors of godparent-like relationships.

So then my point here, and the thesis of this post, is simply that it’s a real shame we don’t have something like godparent like relationships, but for people who would otherwise simply be friends. Maybe we can build back these kinds of relationships somehow. Doing so might cost us a little bit of time and effort, but the reward would be more durable connections with more people.

Thanks for reading to the end of this post. If you’ve enjoyed Nuclear Meltdown, why not send it to a friend?

Friends: Understanding the Power of our Most Important Relationships. Robin Dunbar. 2021. Page 79.

There are a variety of organizations and clubs that might sort of fit the bill. I’m thinking of things like the Rotary Club, for example. But these organizations don’t really impose a firm set of obligations. They have rules and responsibilities of course, but I can also just walk away from them on a whim in a way that I couldn’t with family, or with these other types of relationships I’m describing. More practically, though, such institutions — not just civic organizations but also religions etc — are struggling to maintain membership and stay relevant.

My first thought was that adoption might fit this bill. But while adoption does allow people to induct non-blood relatives into families, once inducted their status is the same as everyone else. That’s great and adoption can be a wonderful thing — I have friends and family who have adopted kids and it was a great experience for everyone involved — but it doesn’t really carve out a new relationship category. More practically, aside from some weird exceptions you don’t typically adopt someone your own age.