Thanks for checking out Nuclear Meltdown. If you haven’t yet, I’d be eternally grateful if you subscribed.

I just wrote about climate change a few weeks ago, but on Monday the United Nations put out a new report that paints a dire picture of the planet’s future. You can see the report itself here, but the gist is that at this point we’ve pretty much locked ourselves in for some negative impacts from climate change.

This got me thinking about one of the underlying assumptions of this Nuclear Meltdown project, which is this: There’s a decent chance that life is going to get harder over the coming decades. And if that’s the case, the people who work together as a family are going to have an even bigger advantage than they already do. In a world where downward mobility is more common, a multigenerational family offers a potential safeguard against each generation being a little worse off than the last.

I’ve previously explored how this idea might work with climate change: Maybe you’ve lived in a nice place and managed to build a good life. But if that place is going to face, say, water scarcity or more natural disasters your kids could follow precisely in your footsteps but ultimately still be worse off.

Climate change is far from the only way that things appear to be moving in the wrong direction.

Take the cost of college. Here’s a chart I made showing the average cost of college going back to 1985. The data is adjusted for inflation and includes tuition, room and board and etcetera other costs. It’s based on data from the U.S. Department of Education1:

The data shows that between the 1980s and now the cost of college has more than doubled. And again, this is adjusted for inflation, meaning college isn’t just more expensive; it also takes a larger share of your income or resources to attend than ever before.

This won’t come as any great surprise to most people. Here’s a 2018 piece from Forbes pointing out that the cost of college rose almost eight times faster than wages. This is a trend that has been widely covered.

But when thinking about my own kids’ prospects, I constantly have to remind myself that that line on the graph is still going up, and probably will for the foreseeable future — making it significantly harder for my kids to pay for college than it was for me, my own parents, or even today’s college kids.

So what does that mean?

In my own case, I went to a very cheap school in the early and mid 2000s. My parents paid for my living expenses my freshman year, while I paid for tuition. After that, I paid for everything via a job, GPA-based scholarships, and Pell Grants. When I finished my formal education, I had no debt2.

That already wasn’t an option for a lot of my friends at other (less cheap) schools when I was in college. And when I look at the chart above, it occurs to me that my own kids probably won’t be able to do what I did. So, I’m going to have to offer them more support than I received just to maintain the same level of opportunity I’ve had3.

The alternative is I give them the same level of support I got, they’re forced to go into debt, and that slows their path to financial stability. In other words, by simply doing the same thing one generation after another, each generation is a little bit worse off4.

Housing offers another example. Here’s a chart that shows the median sales price of a home from the 1960s through now.

These figures aren’t adjusted for inflation, but even when you do adjust for inflation the cost of a home between 1960 and 2000 nearly doubled.

True housing costs are complicated by things like interest rates, which are very good right now but were much more punishing in the 1980s. A few months ago I was wondering about this while doing some unrelated reporting on the housing sector for my job at Inman. Part of my job involves routinely calling up professional economists from companies like Zillow and Redfin, so during one of these calls I asked how overall housing affordability today compares to a generation or two ago.

This economist told me that when you take into account interest rates, incomes and various other factors, housing affordability today is similar to what it was in the 1980s. But, the big difference today is that more of household income is now going to other things like healthcare, student loan debt and other things. In other words, today a family’s financial pie is being cut up into more pieces than in the past, and some of those pieces are getting bigger and bigger — leaving less and less for traditionally big expenses like housing.

It’s also worth noting that home prices in just the last few months have exploded and were up by 22.9 percent across the U.S. between April and June. Did you get a 22.9 percent pay raise this spring? No? Well, then you’re falling behind in your ability to buy housing. (That’s an oversimplification, but the point is that home prices continue to rise faster than wages.)

As is the case with college, this means people in my kids’ generation may have a harder time with housing than my cohort did. And as a parent, that makes me want to find ways to counteract those generational disadvantages5.

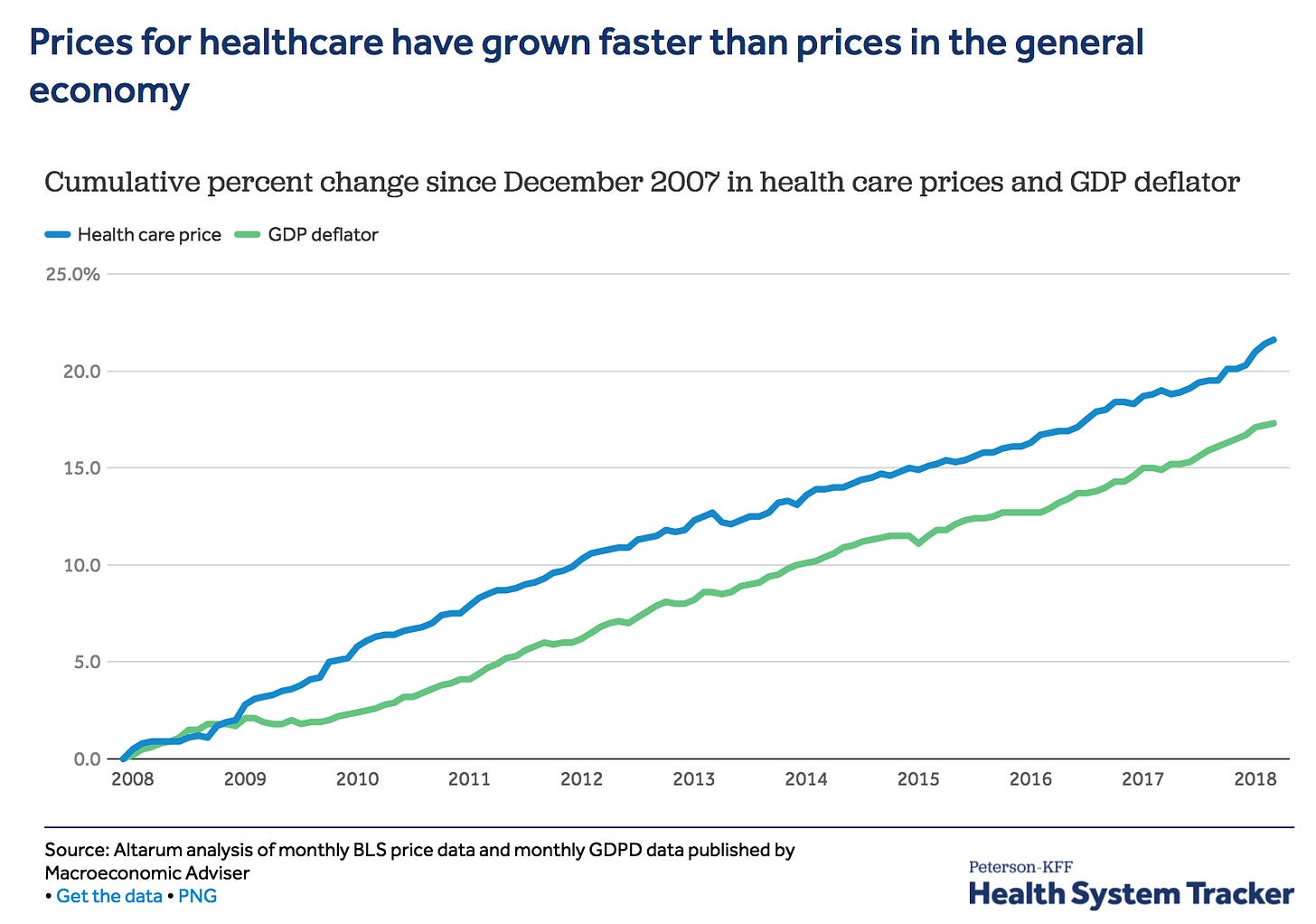

I could keep going and going. Healthcare costs, for example, continue to go up and up. Here’s a graph, and note how it doesn’t have a plateau at the top:

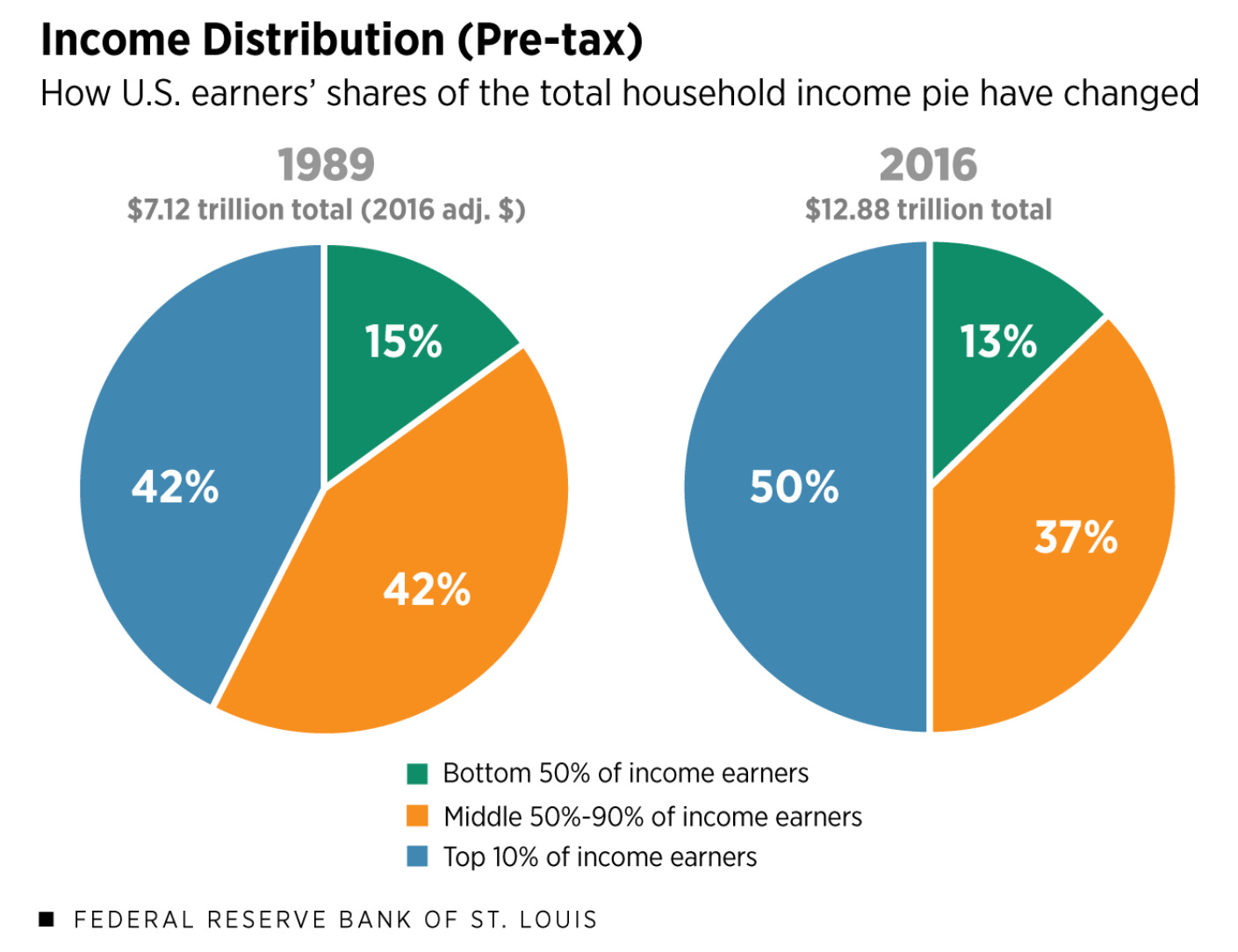

Meanwhile, as I’ve previously written, when adjusted for inflation wages for American workers have stagnated for decades. And at the same time, income inequality has grown.

As a parent, I won’t be able to solve all of these issues for my kids. I could theoretically pay for college tuition if I have enough money, but stagnating wages are a harder nut to crack.

In general though, I believe part of the solution is reorienting my view of parenting away from the idea that my job as a dad is to raise my kids until their 18 or 21, and then basically set them adrift in the world. That setting-adrift philosophy worked well enough in the boom times of the twentieth century. But today it’s unlikely to give my kids even the standard of living I’ve had, let alone enable the kind of upward mobility that’s a foundational part of the American Dream.

In any case, I hope all of these trends — and many others — abruptly reverse. I’d like to live in a more equal society. I’d love it if college was more accessible to more people. I wish healthcare cost less and the supply of homes kept up with demand. I really wish we were doing more to address climate change.

When it comes to voting for political policies, those are the kinds of things I support.

But so far at least, all of these issues are trending in the wrong direction6. And so when I consider the world my kids are likely to inherit, the pragmatic thing to do is assume it’ll be one that is harder, hotter and more expensive — meaning my kids will need multigenerational assistance far more than I did.

All of which is to say, I’m hoping for the best but preparing for the worst.

Thanks for reading to the end of this post. If you enjoy Nuclear Meltdown, consider sharing it with a friend.

Also, please subscribe! It’s free.

Headlines to read this week:

When Is Dinner?

“Beyond the frequency of family meals, new research by Joe Price, Luke Rogers, and me shows that the timing of family dinner is related to how parents and children interact throughout the rest of the evening. Dinner often creates a demarcation in the types of activities families engage in. Before dinner, children often play and do homework, while parents transition home from work and into preparing food. After dinner, parent attention on children is generally high as parents engage in more family-oriented activities. Because dinner initiates family time, parents who start dinner earlier often have more time available in the evening to spend with children before it is time for bed.”

Who Will Take Care of America’s Caregivers?

“The nation’s caregiving work force is fraying. Paid providers are overworked and undervalued, often forced to take on multiple jobs or turn to public assistance just to scrape by. Many family caregivers are struggling as well, sacrificing their own health and well-being to tend to loved ones for years on end. Consistent, skilled, affordable care is in short supply — and getting shorter — and those who provide it are shouldering an increasingly unsustainable burden.”

The data includes single values for the mid 1980s and the mid 1990s, respectively, then jumps to yearly values for the last two decades. You can see the data yourself here. There are also many other similar data sets and charts out there, such as this one, that show the same thing.

I took out a $3,000 student loan when I finished my BA and got married. But because the cost of my grad program was very low, and included teaching opportunities, my wife — who was also working — and I were able to entirely pay that loan off before I graduated with my MA. Obviously, we were very fortunate.

One thing worth mentioning is that I went to Brigham Young University, which is subsidized by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons). That subsidy is likely to exist for the foreseeable future, and BYU will no doubt continue to be a very affordable school. That said, I don’t realistically see my kids attending BYU. And the broader point here isn’t about me specifically, it’s that my generation generally will have had an easier time than that of our kids.

I’ve been using myself as a kind of case study in this post, but obviously I represent a very narrow demographic slice of the country. I had the opportunity to go to college, buy a house, etc. And while I don’t come from a blue blood background, I did have some help along the way, such as my parents paying for my living expenses when I was a college freshman. I’d love to see more people have the same opportunities I did. In the meantime, though, this generational concept would apply across income levels; if college was out of reach for you, and you raise your kids with the same paradigm you grew up in, college will be even more out of reach for them.

An alternative scenario could see my kids generation actually having an easier time in the housing market. Their generation was born over a period that included two major recessions, and which saw significant wage stagnation, and its no surprise the birth rate has fallen. A much smaller generation will be bad news for (eventual) old people like me, but could mean less demand for housing. However, we’ve fallen so far behind when it comes to building new houses that I wouldn’t expect a massive advantage for my kids generation.

Activists insist that there is much we can do to address climate change, which is something I appreciate. I’ve covered climate many times as a reporter, including attending the 2015 Paris Climate Accords. There is indeed much we can do! But realistically we’re not doing much of anything at the moment. The U.S. seems to be pinning its hopes on things like electric vehicles, which are rolling out too slowly and don’t address a myriad of other problems such as low density housing development. Teslas and electric F 150s are cool, but in terms of climate they’re not even close to enough. On the housing front, most U.S. cities continue to be dominated by low density single family homes (I live in one myself). But dense housing is vastly more environmentally friendly. It remains to be seen if Americans en masse will ever embrace Old World-style cities, but I personally don’t think it will happen in my life time or the life time of my kids. All of which is to say, things like NIMBYism don’t make me very optimistic we’ll rise to the challenge of climate change any time soon.