Who will take care of you when you get old?

"If you think your friends are your long-term solution to loneliness, you’re an idiot."

Thanks for checking out Nuclear Meltdown. Please subscribe. Each time someone subscribes an angel gets its wings.

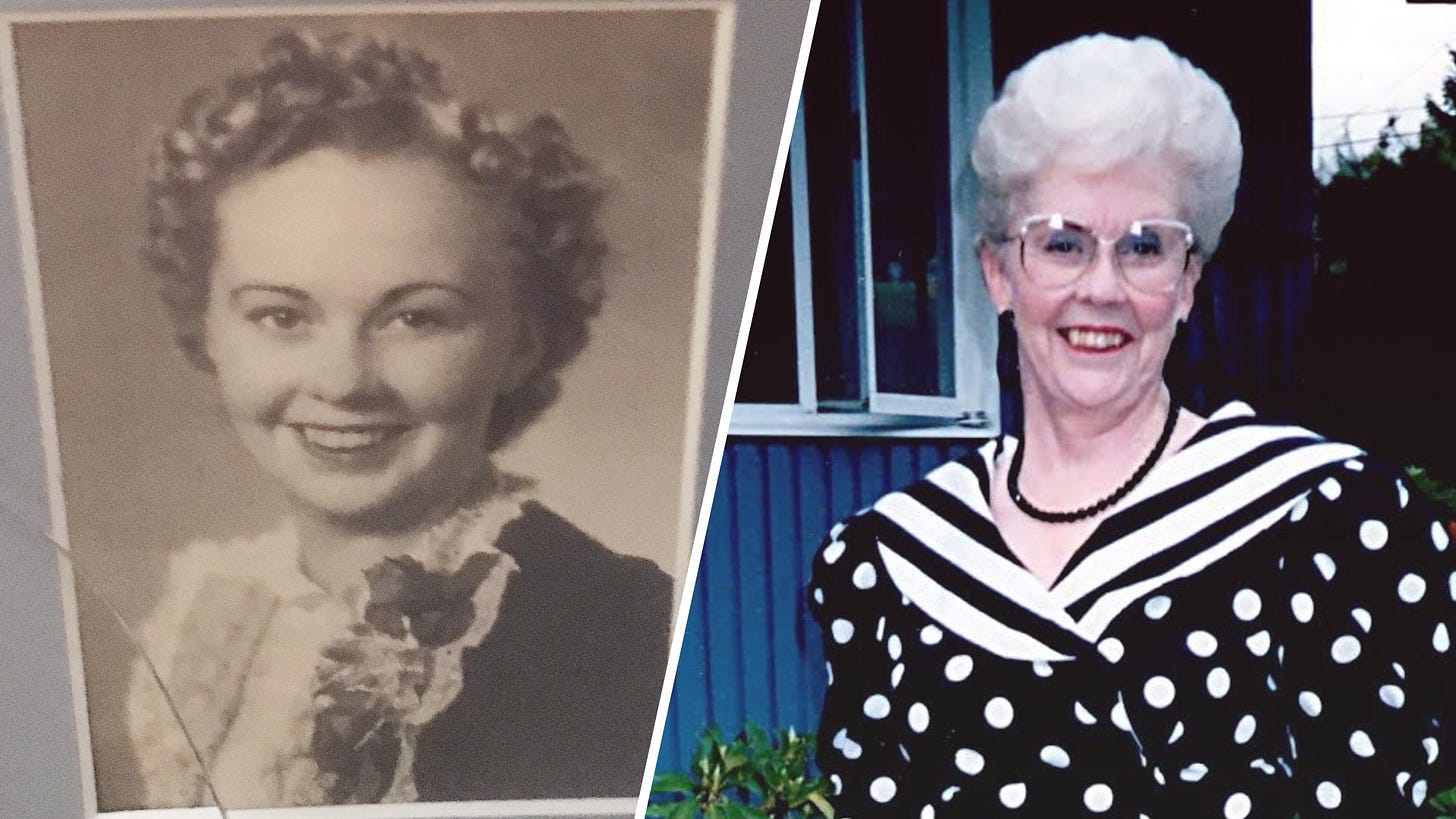

One of the most outgoing and social people in my family was my paternal grandma.

In the years after World War II, her veteran husband — also apparently a skilled card player — came into possession of a restaurant. As my grandma told the story, my grandpa came home one day and announced that she would run it. And she did, becoming a successful business woman at a time when that was unusual.

After my grandpa died — I was 4 years old at the time — my grandma soon met another man while out dancing and they eventually got married. They continued to go out dancing, traveled the world and generally relished the good life. My grandma and both of her husbands faced many challenges that I can only begin to try to comprehend1. I don’t want to ignore that. But at least when I knew her, my grandma was an exceedingly vivacious and warm woman — so much so that I named my first daughter after her in the hope that her colorful personality and adventurous life would be an inspiration.

Like most people, my grandma also slowed down as she got older. Her ability to drive diminished, and with it her ability to live on her own. Eventually, her sons moved her into an apartment at a senior living home down the street from my parents. That happened in 2013 and she lived there until she died in 2019. My grandma experienced the cognitive decline that’s common among many elderly people. But that didn’t happen immediately, and for several years at the senior home she was still her charming self.

Significantly, and despite being a very social person, in my grandma’s final years her entire social circle consisted of younger family members. My dad, her second son, was her most frequent visitor, going over day after day, week after week. Another son managed her finances. Her 17 grandchildren made up a second tier of visitors. Great grandchildren yet another tier.

Alternatively, I never once saw or heard of any of my grandma’s friends visiting. The same thing is true of my other grandparents in their later years, as well as virtually all elderly people I’ve known; I’ve been visiting senior care facilities off and on for decades and I only recall ever seeing family members visiting the residents.

A recent piece in the New York Times similarly pointed out that family members are typically the ones who provide support as people age. But alarmingly, the piece went on to note that there is a growing number of “kinless” older adults — about 6.6 percent of Americans 55 and older — and that people without family die earlier. They also receive “fewer hours of caregiving each week and were more likely to have died in nursing homes.”

“Getting old is hard under the best of circumstances, and even harder if you’re going it alone or with weak social ties,” Dr. Deborah Carr of Boston University told the Times.

Not long after I read the Times piece, I saw that a former colleague of mine tweeted about how nice it was to be an only child while young, but that in adulthood he wishes he had a bigger family support network. And he pointed to this interview in which comedian Chris Rock observed, as I did with my grandma, the realities of aging and family:

The other day I realized I’ve never met an elderly person that was cared for by their friends. Every elderly person I know that’s got any trouble is cared for by a spouse or a child. Sometimes they have like five kids but only one helps. Where are your friends? Your friends are probably not going to be there when it really counts. [Laughs.] When my dad was dying in the hospital, where were his friends? My grandmother, where were her friends? Don’t get me wrong, you get sick in your 20s, your friends will come to the hospital. It’s an adventure. [Laughs.] You get sick in your 60s, they farm it out. “You go Wednesday and I’ll go Sunday.”

Enjoy them while you have them. But if you think your friends are your long-term solution to loneliness, you’re an idiot.

Harsh, but true. Case in point: The Times piece on kinless elders quotes multiple people who are staring into the abyss of aging alone and who feel anxiety because they don’t know what’s going to happen.

Rock’s observation also echoes that of Oxford anthropologist Robin Dunbar, who has noted that the benefits of family grow more pronounced in the “final stage in the human life cycle” when “we start to lose friends through death”2.

That family would take care of aging relatives makes intuitive sense because it has more or less always been that way. But the fact that Rock had to make that point, and that the Times is covering the growing challenge of kinless elders, hints that this concept is not universally accepted. For a lot of complicated reasons, there is an increasingly popular school of thought that does frame non-family as the long term solution to loneliness. For instance, I remember a while back reading a piece about a writer who as a child was inspired by a woman in her community who had no children. The woman opened the writer’s eyes about the many varied paths one’s life can take, including rejecting some parts of conventional family life.

Strong role models are great, and I’m in favor of people doing whatever makes them happy. But I’m also very curious about what happened to the woman later on in old age. Did any of the town kids she once inspired return to take care of her?

The piece never said.

It’s difficult to imagine happy endings to such stories. A person’s independence and focus on self fulfillment may look inspiring at 30 or 40 or 50. But there comes a point when independence is no longer an option and when basic needs trump self actualization. What happens then if you don’t have any family? Really, what’s the solution?

Usually when these questions come up in conversations with friends, I hear things like how we need to create better communities that support a wider range of lifestyles. Fair enough. But the suggestions are vague and seemingly generations away from becoming a reality at any scale. Other times, my fellow millennials simply indicate that they will die before they reach the point where they can no longer live independently. They’re being facetious, but the comments miss the idea that people don’t immediately transition from young and vital to comatose. You might lose the ability to drive at age 70, then go on to live another two decades or more. That can still be a fulfilling and interesting period in one’s life, assuming you’re not living it in isolation.

Family offers an obvious solution here because it spreads relationships out over time. Ideally, adult children take care of aging parents, and their own children see that process and prepare for their own time at bat3. How do you replicate that either with friends or institutions? I don’t know many people who have close friends decades younger than them4. And friends in a person's same age cohort are likely to be experiencing limited mobility and other issues at roughly the same time; my grandma's friends probably didn't visit her because they couldn't get out, or because they were dead.

Alternatively, with enough money you can certainly pay for nurses and caregivers, but you still need a social circle. You still need loved ones.

I began this post with the story of my grandma, but I want to conclude with an even older tale: In the early 2000s, archeologists working in the country Georgia revealed they had discovered the skull of a male Homo erectus. The skull was 1.77 million years old. But what made the skull really remarkable was that it was missing all but one of its teeth, and that the individual apparently lost his teeth while he was still alive. He then went on to live long enough that the bones grew in around where his teeth had been.

Animals that lose all their teeth and can’t eat soon die. So what this toothless skull seemingly revealed was that human ancestors deep in the past were taking care of each other. The skull belonged to someone who required a caregiver. Reports at the time described the finding as exposing the “roots of compassion.”

We can only speculate about what that individual’s life was like, but it’s clear that humans and human ancestors have been caring for each other for eons. We literally evolved to do this. And for most of that time, families and tribes have played the primary role in elder care. Maybe there are other solutions to be found. Maybe there’s a radically different world waiting for us just over the horizon. But as I gaze into my own future, I’ll place my bets on family as the solution to long term loneliness.

Thanks for checking out Nuclear Meltdown. If you’ve enjoyed this post, please consider sharing it.

Correction: The story at the beginning of this post is about my paternal grandma. Initially I wrote that she was my maternal grandma. Not sure how I didn’t catch that.

Both of her husbands, my grandpas, were World War II veterans, for example.

Friends: Understanding the Power of our Most Important Relationships. Robin Dunbar. 2021. Page: 147

Obviously there are plenty of families that don’t step up and don’t take care of each other. But the fact that the elderly have existed throughout human history indicates that on the whole the family solution does work, even if individual tribes sometimes treat each other badly.

Not only that, but it’s generally frowned upon for people who are, say, 35 or 40 to befriend someone who is 15 — even though that’s the kind of age gap you need to do elder care. And if you try to wait until later, it’s going to be harder to build the relationships. Imagine being 65 and trying to make a 35 year old friend who would be willing to take care of you in old age. There’s a reason friend relationships don’t work for this issue.

I think the assertions in this piece are based on the older versions of friendship. These days, many younger LGBTQ people (like, under 60) have built "chosen family" systems that are impressively tightknit. I also know others who have small families but are very close to certain friends and see them frequently as a support group. We don't yet have stats for the ways that these chosen families will support their peers. I'd also look to certain church groups (Unitarian, Quaker, Episcopal) and the networks they create. I agree that we have to think ahead, and staying close to family isn't a bad idea if they are kind to others in their family, and that it can help (in some cases) if we see family frequently and are less often in touch with them at a distance. But it's important to note these other, emerging networks, I'd say.