Thanks for checking out Nuclear Meltdown. If you’ve enjoyed this blog, consider subscribing.

A few weeks ago I was scrolling through my Twitter notifications when I saw a response to a blog post I wrote about having children. My title asked, “why bother having kids?” and the tweet offered a blunt answer: “Most people shouldn’t.”

There are lots of trolling comments out there, but this one caught my eye because it seemed to capture a general anti-kid sentiment that’s pretty common online. Scroll through Twitter for a few minutes and you’ll see plenty of other comments in this vein. Which is fine. To each their own.

But it also caught my eye because I had recently read a blog post from the writer Freddie deBoer in which he noted that the idea of “family abolition” appears to be “gathering steam among academic leftists.” DeBoer — who was critical of family abolition — summed up the idea as the belief that “the family is an inherently oppressive structure” and “that we should get rid of it.”

I probably would have forgotten about all of this, except that shortly thereafter I was reading this post from Anne Helen Petersen. The post introduces readers to a book on estrangement that apparently1 makes a provocative claim: “compulsory kinship” — or in other words what we think of as family — is “at once insidious and deeply damaging.”

DeBoer is a polarizing leftist who is somewhat unpopular among much of the professional media class, but Petersen is a respected mainstream journalist with whom I was colleagues at BuzzFeed News. And after encountering all these examples of relatively negative takes on the conventional idea of family, I began to wonder just how much traction family abolition was getting in the mainstream.

DeBoer had linked to an upcoming course at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research called “What is Family Abolition?” The course description states that “the abolition of the family has long been a demand of Marxist and socialist agitation. Marx and Engels called for family abolition in the Communist Manifesto.” The person teaching the course, Sophie Lewis, has also written a book on family abolition, which The Nation covered in 2019 and Vice covered in 2020. The Vice article was titled “We Can't Have a Feminist Future Without Abolishing the Family.” Vice and The Nation are decidedly left leaning, but they too also aim for a more or less mainstream audience. These aren’t, like, obscure anarchist zines that a protester hands you at 2 a.m. after you’ve been tear gassed.

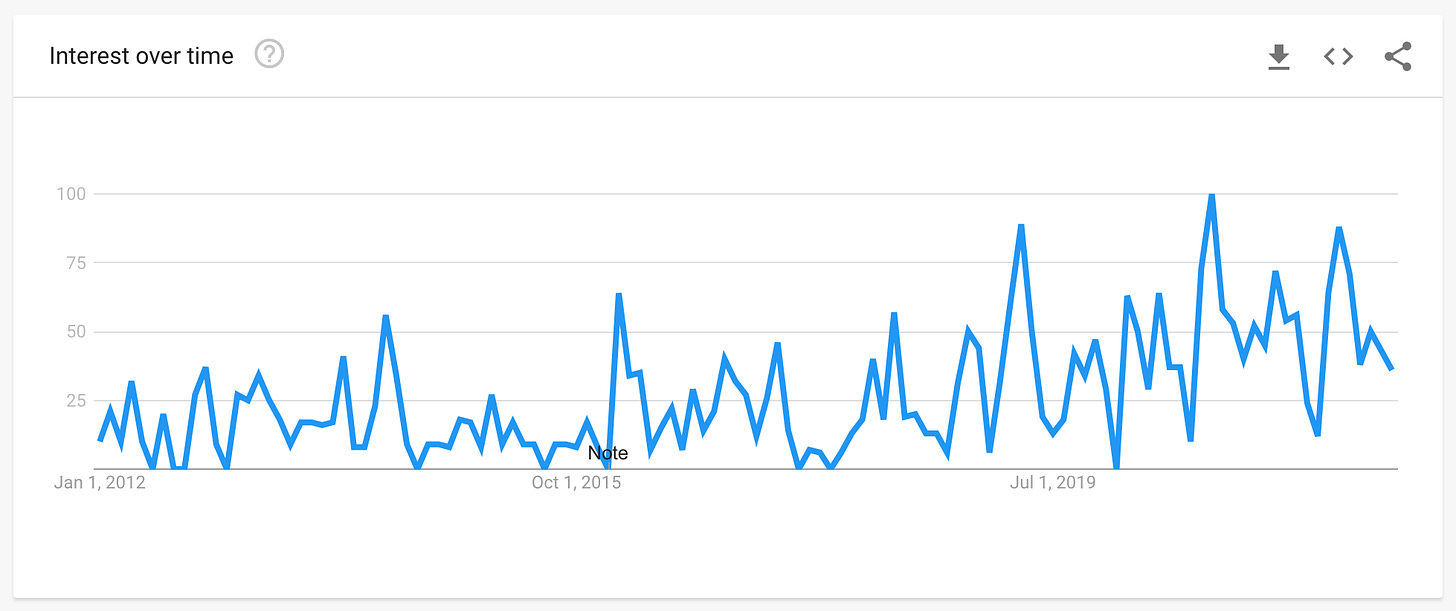

I also did a quick Google Trends search for the last 10 years, which seemed to suggest “family abolition” is experiencing an upward trend when it comes to internet search traffic.

All of this is a long set up to make a simple point: It kind of does seem like the traditional idea of family is under attack2. Not in the sense that people want the definition of families to evolve, a la same sex marriage, but in the sense that they want to get rid of families altogether3. And that attack seems to be gradually moving from the edges of the fringe left to the somewhat more mainstream left.

So why does this matter?

Three reasons come to mind. First, if family abolition is picking up steam that speaks to a broader feeling that families as they currently function aren’t working for a lot of people. I know “abolish the family” is going to sound to a lot of folks like something a cartoon villain might say, but I don’t think the people making these arguments are bad people. I think they’re seeing a lot of real problems with families — problems that I agree exist4 — but coming up with policy conclusions that I strongly disagree with.

Second, family abolition strikes me as absurdly impractical at anything beyond the individual level. In other words, you or I may cut off toxic family members, but society as a whole is just never going to buy the idea that family, as a concept, is insidious.

As it turns out, family abolition is an old concept. As that Brooklyn College course description indicates, it has long been associated with Marxism. Marx and Engels didn’t invent family abolition — other socialists and radical thinkers of their day weighed in as well — but they did imagine a society where relationships “would have little or no resemblance to the family as it existed in nineteenth-century Europe or indeed anywhere else”5. The duo also supported the idea of taking kids out of family settings and having them raised in public institutions, of abolishing inheritance, and of changing marriage from a legal arrangement to a purely private one6. Ultimately Marx and Engels “were unrelenting in their assault on the contemporary condition of the family” 7, according to historian Richard Weikart.

But these ideas are really hard to pull off in the real world and at scale. In the USSR, for example, the Soviets implemented a variety of policies meant to weaken the traditional idea of the family. Many of these policies are tame by today’s standards — divorce got easier, couples could take either person’s last name, etc. — but the idea was to help old systems like the family and the state “wither away.” However, over time the Soviets had to roll these policies back because they needed more workers, had too many kids to take care of, etc. And then when the USSR collapsed, the oligarchs took over. So, arguably the most famous real-world experiment with Marxism devolved to the point that Russia spent decades dominated by an exceptionally traditional — and probably for many westerners, undesirable — version of family8 that was closer to the old aristocracy than anything Marx had dreamed of.

Other experiments with Marxism have played out differently, but the point is that people have attempted to abolish the family in the past and it didn’t work9. Which makes sense; I’ve mentioned this many times before, but “kin-based institutions are perhaps the most fundamental of human institutions”10 — meaning we’re hardwired to function in family units. That’s hard-to-impossible to fight over the long term, and even deBoer — again, a leftist himself — described being anti-family “as looking for the thing that will piss the most people off, for the least possible political gain.”

Finally, and third, radical long-shot provocations are distractions from more doable solutions. To be anti-family is to take the most extreme position possible. It’s like finding out your house has some flaw — maybe the roof is leaking or there’s a crack in the foundation — and instead of fixing the problem you decide to burn the entire house down. And then you decide to burn down every house, because the failure of your home is somehow an indictment of the very concept of houses in general.

This is a silly analogy, but it’s not much of a hyperbole; families are at least as old and fundamental to human society as houses. And it’s equally nonsensical to give up on either of them, even if there’s ample room for improvement.

This is why, for example, I quote often from Fault Lines: Fractured Families and How to Mend Them by Cornell sociologist Karl Pillemer. Fault Lines acknowledges the reality of estrangement and offers no judgement on people who are estranged themselves. But its operating with the idea that estrangement, overall, is an unfortunate thing that’s worth trying to minimize. In other words, there may be many necessary individual estrangements, but the overall goal of the society should be to make estrangement less common — not universal, which is what the anti-family cohort often comes across as wanting.

Ultimately, I’m not worried about the anti-family movement successfully dismantling families. It’ll always be a niche idea. But I am troubled by the prospect of radical long-shot ideas shifting the discourse away from things that could actually happen. And I’m concerned that a sense of the family being under attack could prompt a backlash that entrenches what we have now in a way that makes it more difficult to make positive change in the future.

In the end, families may not be perfect, but in practice they’re not going away and may be the best thing we’ve got.

Thanks for checking out Nuclear Meltdown. If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, I’d love for you to subscribe. It’s completely free.

Headlines to read this week:

A Creative Solution to ‘the Friendship Desert of Modern Adulthood’

“When I moved to California with my husband and my six-month-old, I really struggled meeting friends. All parents wanted to talk about was their kids. I wanted to have something else to talk about. I was like, Where’s my village?

I tried all these different community-building activities. I combined activism with hanging out with friends. I organized weekly potlucks. At one point I put an ad on Nextdoor and got our neighbors to go for a walk and get to know each other better. But I still didn’t have many intimate friends.

That’s how I came up with the idea of arranged friendships. I grew up in Iran, and I knew many old couples who had happy and loving arranged marriages.”

I haven’t read the book myself. I did add it to my list, but realistically there are a lot of books on that list, most of them more in line with the perspective I’m arguing for in this newsletter. So it may be a very long time before I get to it.

When I say “attack,” I mean people who literally are arguing for the end of families as we know them, not those who want the definition of family to evolve — which is always happening anyway and always has. Change isn’t necessarily an attack. An attack is an attack. Relatedly, it's worth noting here that I’m always skeptical of claims that the “family is under attack.” This skepticism goes back to when I was a teenager and the “family-under-attack” argument was deployed by members of my community to oppose same-sex marriage. In the end same sex marriage became legal, yet none of the dire predictions I heard came true. If anything, there are now a lot of same sex couples living fairly conventional, nuclear family lives — suggesting marriage equality actually entrenched the idea of family even more than it already was.

I don’t think it’s a stretch to argue that family abolition is actually the opposite of the argument in favor of same sex marriage. The former argument wants fewer familial ties, the latter more.

Nuclear Meltdown — this very newsletter — could be thought of as a kind of attack on the family in the sense that the underlying thesis here is that nuclear family, specifically, isn’t enough. The difference, though, is that I suspect solutions lie in historical examples, while family abolitionists want to try something new.

“Marx, Engels, and the Abolition of the Family.” Richard Weikart. History of European Ideas, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 657-672, 1994. Page 658.

“Marx, Engels, and the Abolition of the Family.” Richard Weikart. History of European Ideas, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 657-672, 1994. Page 665.

“Marx, Engels, and the Abolition of the Family.” Richard Weikart. History of European Ideas, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 657-672, 1994. Page 659.

Like many of us, I had plenty of late night conversations in college about what counts as real communism, socialism, Marxism, etc. Obviously, all the real world experiments fall far short of what Marx and Engels envisioned. But it’s also fair to say that the early communists were at least more interested in implementing Marx’s theories than, say, most twenty first century Americans are. In any case, I get how reading Marxist theory can be thrilling. It’s simultaneously nerdy, provocative and dangerous-feeling all at once. But it just has a really terrible track record in the real world.

Family abolition gained some steam in the US in the 1960s and 1970s. But if fell out of favor as the radicalism of those decades gave way to the conservatism of the 1980s and 1990s.

“The Origins of WEIRD Psychology.” Jonathan Schulz, Duman Bahrami-Rad, Jonathan Beauchamp, and Joseph Henrich. June 22, 2018. Page 3