The Nuclear Meltdown philosophy

Here's an attempt at pinning down an ethic after a year of writing this newsletter

Thanks for checking out Nuclear Meltdown. If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, consider subscribing.

I recently received an auto-generated email from Substack congratulating me on maintaining this newsletter for a year. I hadn’t realized it had been that long, so I’d like to thank the bots of Substack for the reminder.

Additionally, my wife and I are still expecting our third child. The due date was Monday, so we’re already several days overdue at this point.

All of this made me think that now might be a good time to take stock of what this newsletter is about and to try to articulate a specific overarching thesis. Pinpointing some set of values — a specific ethic, if you will — was always an objective here, but I don’t think I’ve distilled the underlying assumptions into one place before. This is of course a work in progress, but here’s what I’ve got so far:

Family is an effective social organizing unit

There are a lot of problems out there. People lack adequate childcare. They have too few job opportunties. Housing is too expensive. There’s a loneliness epidemic, which is acute among groups such as seniors, but also affects all of us who feel like we have far fewer closer friends as adults than we thought we would.

The list could go on, but the argument of this newsletter is that family, specifically, is the primary practical solution for these problems. Friends, social programs, and long-shot ideological shifts1 might be nice, but family is the place to start.

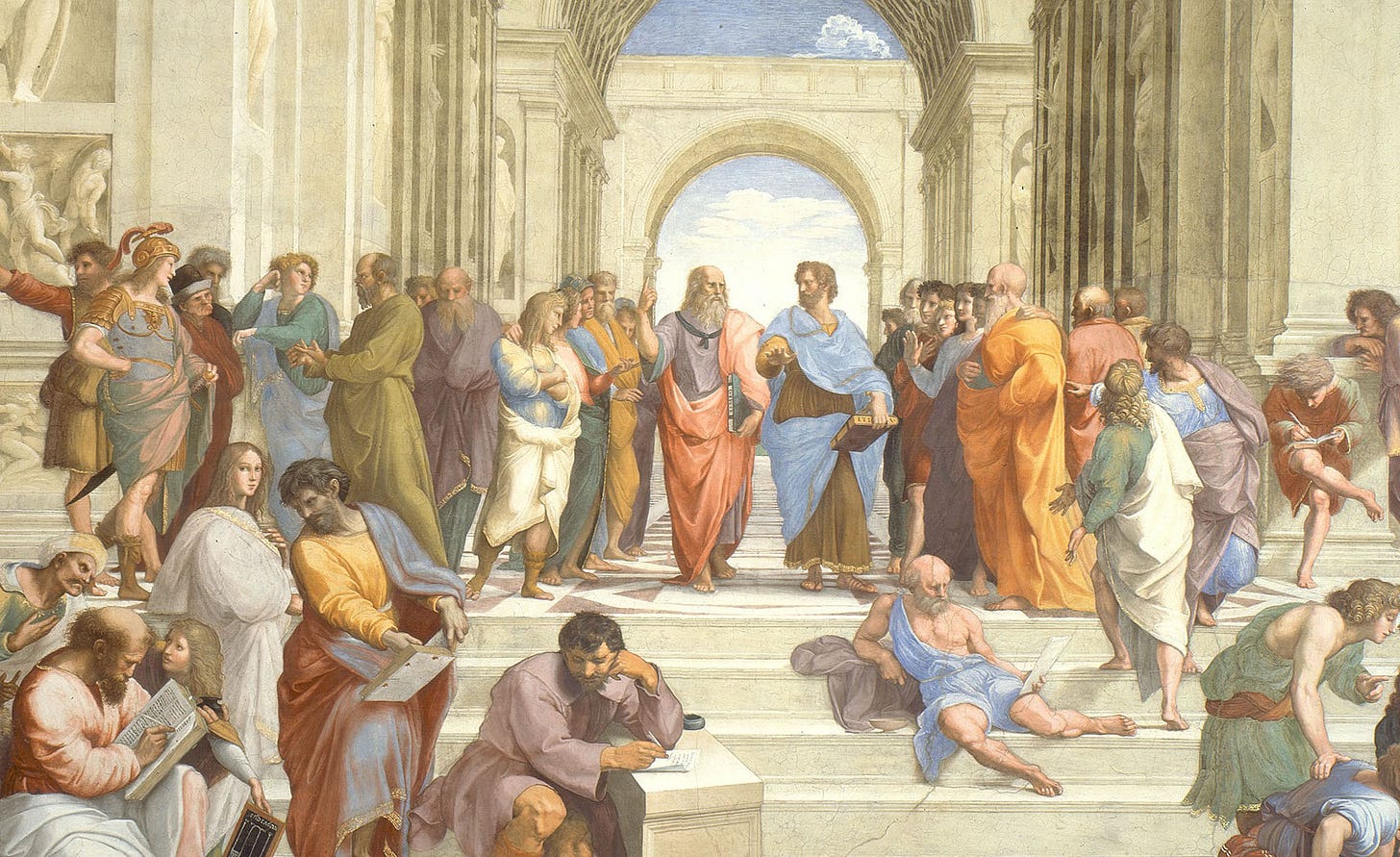

Why? Part of the logic is that family has been the basic organizing unit for most of human history. It cuts across time periods, cultures, and locations. As I’ve mentioned before, “kin-based institutions are perhaps the most fundamental of human institutions”2. We know it works.

Another part of the logic for me is my relatively low level of confidence in systemic improvement on issues3 I care the most about.

Of course I’m interested in those other topics. I’ve written repeatedly about friendship in this newsletter. And as the father of two (soon, three) small children, I’d love some sort of subsidy that would make childcare less burdensome. Figuring these things out is all part of what I’m exploring here.

But family is the key4.

I know this isn’t necessarily a popular idea because many people don’t get along well with their families. In a world in which family bonds are entirely based on emotional connections, it’s very easy for those bonds to whither away. And that brings me to the next point.

Emotional bonds are nice. Financial bonds are stronger

A while back I wrote a series of posts on money and financial independence. The idea was that over the long term it’s probably better to be an asset holder than a high wage earner.

Some folks pointed out that I was essentially making the same argument that other financial independence movements advocate, for example the FIRE movement5. And in practice that’s more or less true. Life is indeed going to be easier over the long run if you’re smart with your money and invest6.

But I think where this newsletter differs from other financial independence texts is in the ultimate objective. What I’m interested in is building a multigenerational financial engine that benefits my family even after I’m gone. In other words, I’m less concerned with, say, my own retirement and more with how my decisions will impact future generations’ housing options, job prospects, etc7.

The other component here is financial intertwining between generations. The most basic way to think about this is with housing; if two generations live in the same house they both save money. And they have a greater incentive to tolerate each other. Similarly, if you stand to inherit the family business, you have a financial incentive to put up with your family in ways that you might not if you’re relationship is purely emotional. Even just working in the family business is going to increase the amount of time spent with family members, and as I’ve written before time is a key part of forming deeper bonds.

One of the most-read posts I’ve written for this newsletter was about how “love is overrated,” and my point was that emotional bonds are great and rewarding and nice. But they’re also fickle, easily broken, and a relatively new way to think about relationships. For much of human history, your survival, success and happiness depended on how your family used resources. My hope is that this idea can still work, and that as a family strives together financially it ends up with greater incentives to make emotional relationships work well too8.

Place is important

Like a lot of us, my friends and I all moved away from each other in our 20s. We mostly all were pursuing jobs, affordable living, etc.

But the cost was high. Not just the literal cost of living in my expensive coastal city, but also the externalities. I had fewer friends in my daily life. If I needed a plumber or an honest mechanic, I couldn’t call my parents or friends to use their guy. If I needed a babysitter — well, we basically just never used a babysitter because we didn’t have one. We lacked a network.

There’s no question that moving to big job centers is a good career move for ambitious young people. But in my experience, chasing job opportunity meant sacrificing community. And while the value of community is hard to quantify, there’s no question that it is valuable.

Ergo: place matters. It’s worth putting down roots somewhere and building that network. It’s going to be beneficial for whoever builds it, and it’s also something that can be passed along9. I’m not suggesting everyone needs to stay in their hometown. Choosing a place with good prospects is also important. But I’ve found it nearly impossible to build the type of network I want in just a few years. I suspect it takes decades, or even multiple lifetimes, of ongoing investment in a single place.

A long-term mindset benefits everyone

I’ve repeatedly written about having a long-term mentality, including a post last year in which I explored how my own family diverged over the last century and a half. The branches of the family that worked together over multiple generations have more opportunities and are financially more secure than the branches where everyone pursued their own self interest and started from scratch each generation.

The analogy I’ve mentioned before is that of a tree farmer: Trees can take longer than a generation to grow, meaning that a tree farm works if people work together across time. One generation harvests what the previous generation planted. And so on.

In the US, most of us aren’t the beneficiaries of multiple generations of good decision making. The American ethos values self-made people who pulled themselves up by their bootstraps. And even if that idea is mostly bogus in practice, it offers an excuse to not really think too deeply about how subsequent generations will make their way in the world.

I want to break that cycle in my family, mostly because I can see examples all around me of people who don’t have that mentality. And it’s clear that they benefit thanks to the long-term thinking of their predecessors10.

See yourself as the founder of the family

The most common pushback I’ve had to this newsletter is from people pointing out that their families don’t have a multigenerational mindset. So, I’ll write about childcare, and then someone will be like, “but my parents don’t want to help me with my young kids.” Or I’ll write about housing, and someone will say, “but my family didn’t buy me a house.”

And yeah. Thanks to that pesky bootstrapping ethos, that’s most Americans. If you weren’t born into a family that already had a multigenerational mentality, its unlikely you’ll persuade people in the autumn of their lives to completely reorient their values. It’s too late.

But that doesn’t mean it’s too late for our kids or grandkids. What I’ve realized is that we don’t have to be sidekicks in our parents’ or grandparents’ story. We can be the protagonists11.

So, I may not have had a job waiting for me when I reached adulthood. I may not have learned anything about financial planning until my 30s. I may not have an ancestral home or a family trust. But I can set the ball rolling so that subsequent family members are more likely to have those things. Maybe I’ll succeed. Maybe I’ll fall short. But the point is that I’m taking the first steps in a journey.

Thanks for reading to the end of this post. If you’ve enjoyed Nuclear Meltdown, consider sharing it with a friend.

Note: My wife and I are going to be having a baby any day now. That may disrupt the publishing schedule of this newsletter somewhat. Bear with me.

Sometimes when I debate these ideas with people we end up going down a rabbit hole that ends with a comment like, “well, that’s why we have to get rid of capitalism.” I enjoy provocative debates as a mental exercise, but ending capitalism is obviously not a practical solution that’s going to happen any time soon. If the only way we solve our problems is ending capitalism, then we’re stuck with our problems. I’m much, much more interested finding ways to live a more fulfilled life that don’t require chasing quixotic lost causes.

“The Origins of WEIRD Psychology.” Jonathan Schulz, Duman Bahrami-Rad, Jonathan Beauchamp, and Joseph Henrich. June 22, 2018. Page 3

Housing is a good example: When I started looking to buy a home in LA in 2015, the market seemed out of control. Many people I knew said they were just going to wait out the craziness and buy when the bubble popped. But fast forward to today, and the situation is vastly worse. Even if there was a Great Recession-type bubble, prices would not fall back to their 2015 levels — meaning everyone who has been priced out for years would still be priced out. It’s also my job to talk to economists about the housing market, and none of them see a bursting bubble on the horizon. At the same time, NIMBYism on both the right and the left is creating a stranglehold on construction in existing neighborhoods. All of this leads me to conclude that there’s a good chance the housing market my kids face will be significantly more brutal than the one I faced. I hope that’s not the case, but I’ll prepare for the worst. I’ve seen this same trajectory on numerous other issues.

I was recently exposed to the idea of “subsidiarity” thanks to the newsletter The Liberal Patriot. The gist of this idea is that its best to solve problems at the most local level possible. So, if a family can solve a problem, its better to tackle it that way than, say, at a municipal level. If a community can solve a problem, it’s better to do that than to solve it at the federal level. And so on. It’s a kind of local-first approach to problem solving. I’m relatively new to this concept, but it seems in line with the family-as-an-organizing unit argument I’m making here.

I tend not to follow a lot of financial gurus because… I’m not really sure. I want to say it’s because so many of them seem like sleezeballs who are constantly thumping their chests about all their financial victories. But I know there are people who aren’t like that. I think it’s partly my humanities bias. Why read a book like Rich Dad Poor Dad when I could read, say, The Grapes of Wrath? Coming from the humanities, I’ve probably internalized a sense that the noblest life is the life of the mind, and that it’s best to be above the vulgarity of financial advice books. I mention this because I think this is a highly counterproductive attitude to have, and this life-of-the-mind mentality is something I’ve actively had to make myself let go of — or at least to balance out with a more practical attitude. I also think this is a fairly widespread attitude, both among my fellow humanities graduates and among a certain type of professional class knowledge worker.

The follow-your-dreams and do-something-you-love mantras I heard growing up were probably the worst advice I’ve been given because they actively encourage you to disregard financial concerns.

I obviously don’t claim to have invented this idea. Instead, I realized the value of multigenerational financial thinking after watching peers pull ahead financially and professionally thanks to huge advantages they received from their families. I’d love to live in a more equal world, but in practice I have to think about whether I want my own kids to have those kinds of family advantages or not.

I know we’ve all heard horror stories about families who worked together and then had a falling out over money. Certainly there’s risk involved. But life is risk, and there are at least as many examples of this idea working as there are of it failing. I’ve written about some of them here. And just because something might fail doesn’t mean it will, or that it’s not worth trying to begin with. The alternative is every generational starting from scratch.

When I was a kid, some of my best and closest friends were the children of my parents friends. I inherited friends thanks to my parents’ network, and my life was richer as a result.

I know this is a hard sell. I’ve deliberately tried to structure the arguments in Nuclear Meltdown around selfishness. My posts are trying to make the case that your life will be better with a multigenerational mentality. You will be happier. You will be richer. Whatever. I’m making arguments in this way not because I’m pro-selfishness, but because I think people (definitely me) are generally self interested and it’s easier to see the value of something that directly impacts us. The long term mindset strays somewhat from that idea because no one is going to be around to see what their great great great grandchildren are doing. So this is something of an altruistic appeal. I’m trying to convince myself here to do something for the greater good.

A while back I wrote about how the TV show Modern Family explores the multigenerational concept. I think for a lot of people in my age group, we identified most with the middle generation, Claire and Phil Dunphy, or (depending on when we saw the show) the Dunphy kids. But as I’ve thought about this concept, the character that’s most relevant is the grandfather, Jay Pritchett. He is the one who founded the family and laid the groundwork for its subsequent success.